This piece questioning if longer working lives are possible for all workers is the first of a series of perspectives on labour market inclusion, written by Dr Iuliana Percupetu from the University of Bucharest. Dr Precupetu is a sociologist specialising in quality of life, social and health inequalities, and older age social exclusion. She is a senior researcher with the Research Institute of the University of Bucharest.

In 2022, the range in normal retirement ages* among the European countries varied between 62 years (in Slovenia, Luxembourg and Greece) and 67 years (in Norway, Denmark and Iceland) for men and between 60 years (in Poland) and 67 years (in Norway, Denmark and Iceland) for women. It is expected that in countries like Sweden, Denmark, Estonia and Italy the normal retirement age will increase to 70 for men and women who start their career in present days, provided that life expectancy will raise according to projections and links with life expectancy implemented (OECD 2023).

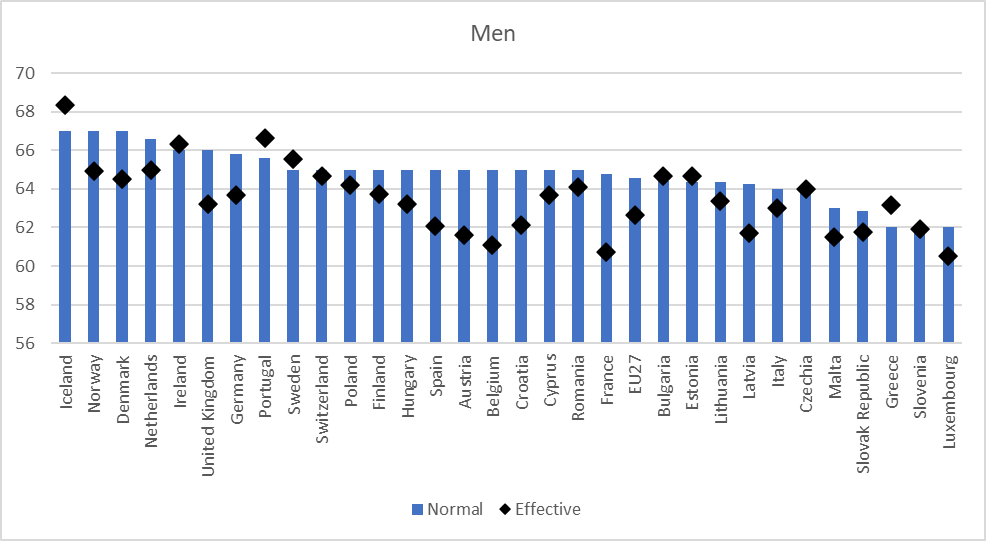

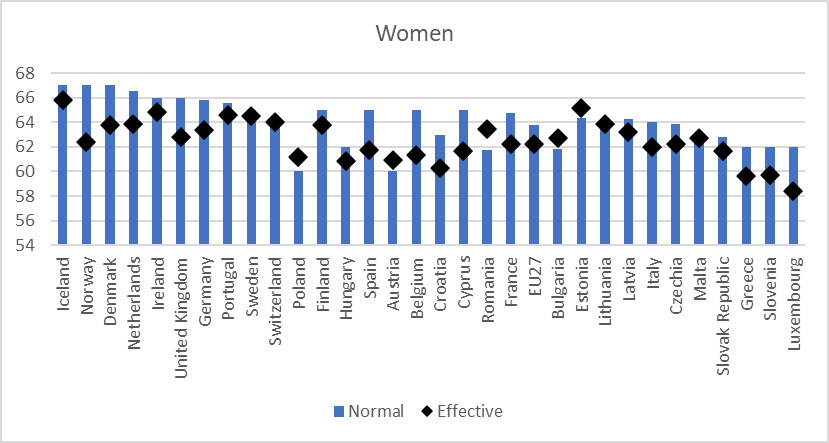

These current trends in prolonging working lives are substantiated by increasing longevity and the fact that the average effective age of labour market exit is still lower than the normal retirement age in most European countries. Life expectancy at 65 increased in all EU countries from 2000 to 2022 with at least 0.9 years in Lithuania up to 4.1 years in Ireland (Eurostat, 2023). Effective retirement ages remain lower than the normal retirement ages for the majority of EU countries, with some states showing larger differences, while others displaying smaller gaps between the two (Figures 1 and 2).

The implemented pension reforms conducted to significant progress in extending the time in the labour market for older people. The employment rate of 55–64-year-olds in EU27 nearly doubled, from 38.1% in 2004 to 63.9% in 2024, with some countries reaching rates as high as 75% (Netherlands) and 78% (Sweden). Still, it is considered that more needs to be done.

Despite developing policies focused on lengthening working lives and their subsequent progress, it becomes apparent that they cannot equally reach all population groups. Substantial socio-economic inequalities that persist in numerous societies represent a challenge in achieving longer working lives.

Many European countries are trying to close the gap in retirement age between men and women. However, women have a more vulnerable situation on the labour market than men, which might still determine them to retire early. Studies show that women have rather discontinuous career paths due to caregiving roles and family responsibilities, are more involved in precarious types of work (Phillipson, 2020), are more employed in jobs at high risk of automation and have lower lifetime earnings than men (OECD, 2019). Furthermore, women are involved in intensive caregiving in their older years either for partners or grandchildren, especially in countries with less developed services, adding additional pressures around the time of their retirement. In fact, women cite as reasons for exit from the labour market predominantly care responsibilities, while men invoke disability and unemployment (OECD 2017).

Low-income, low-skilled older workers also face important challenges in working longer. Although driven by financial need to remain active in the labour market in their later life, they are also employed in more precarious jobs, have higher risks of poor health and suffer from work strain (e.g. Murtin et al. 2022). They also have a shorter life expectancy at 65 of up to five years in comparison to higher skilled (Mosquera et al. 2019), translating into less time spent in retirement. Even when they retire, they might be forced to take up jobs to supplement inadequate pensions.

Similar challenges arise for other vulnerable groups like older workers with poor health, those with disabilities, or those with an immigrant status.

Given the increasingly fragmented and precarious nature of employment, it is highly likely that precarious employment trajectories translate into precarious retirements for many groups. Older age itself posits unique issues in terms of poor health, lower levels of physical and social activities, and negative life events like becoming a widower. Moreover, for vulnerable groups, disadvantages tend to accumulate over the life course, making a disproportionate impact in older age on their quality of life. Under these circumstances, vulnerable older workers run the risk of being trapped in an area of precarity marked by declining incomes and limited opportunities to access suitable jobs (Phillipson, 2020). At present, retirement transitions in many countries are marked by inequality and while longer working lives remain a goal, better and longer working lives should be a policy ambition.

*The normal retirement age is defined as the age at which individuals are eligible for retirement benefits from all pension components without penalties, assuming a full career from age 22 (OECD, 2023: 42).

Figure 1. Average effective age of labour market exit and normal retirement age in 2022 for women

Source: OECD 2023 StatLink https://stat.link/9zyo7u

Figure 2. Average effective age of labour market exit and normal retirement age in 2022 for women

Source: OECD 2023 StatLink https://stat.link/9zyo7u

References

Eurostat 2023 (demo_mlexpec)

Mosquera, I. et al. (2019), Socio-Economic Inequalities in Life Expectancy and Health Expectancy at Age 50 and over in European Countries. Socio-Economic Dimensions in Extended Working Lives, Sozialer Fortschritt, Vol. 68/4, pp. 255-288, https://doi.org/10.3790/sfo.68.4.255.

Murtin, F., et al. (2022), The relationship between quality of the working environment, workers’ health and well-being: Evidence from 28 OECD countries, OECD Papers on Well-being and Inequalities, No. 04, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/c3be1162-en.

OECD (2017), Pensions at a Glance 2017: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/pension_glance-2017-en.

OECD (2019), OECD Employment Outlook 2019: The Future of Work, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9ee00155-en.

OECD (2023), Pensions at a Glance 2023: OECD and G20 Indicators, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/678055dd-en.

Phillipson, C. (2020). Reconstructing Work and Retirement. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics Vol 40 Issue 1, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1891/0198-8794.40.1