This piece discussing the gender gap is one in a series of opinion pieces on labour market inclusion. The piece has been written by Dr. Dominik Buttler. Dominik Buttler is an Associate Professor in the Department of Labour and Social Policy at the Poznan University of Economics and Business, and a Research Fellow at the Institute of Sociology at Leibniz University Hannover. His research interests include labour economics, with a focus on school-to-work transitions, labour market discrimination, and happiness economics. In the PATHS2INCLUDE project, he is responsible for conducting a factorial survey experiment on organisational determinants of discrimination in hiring.

According to research by Nobel Prize-winning economist Claudia Goldin, occupational segregation—the fact that women and men tend to choose different occupations—is becoming a less significant factor in explaining the gender wage gap. In developed economies, two-thirds of the wage gap now stems from differences in earnings within the same occupations.

Why is that? The key lies in a specific feature of jobs: their level of “greediness”. Greedy jobs demand long hours, work on weekends, and availability on short notice. This “greediness” is not limited to one sector or profession—it spans across industries. Within the same occupation—for example, lawyers—we can find greedy roles, such as those involving intense collaboration with international clients, last-minute meetings, and frequent business travel. But there are also quieter lawyer job positions that are more predictable, have standard working hours, etc.

The wage gap widens when children enter the picture. Women typically take on a larger share of caregiving responsibilities. Greedy jobs are incompatible with balancing work and caregiving, which is why fathers are more likely than mothers to take on such roles. Naturally, greedy jobs—being more demanding—also tend to be better paid.

Our research in the PATHS2INCLUDE project set out to test whether Goldin’s theory could be extended beyond wages. Specifically, we wanted to investigate whether job greediness plays a role already at the recruitment stage. Are recruiters, when hiring for a greedy job, less likely to hire candidates with caregiving responsibilities?

In our experiment, we surveyed over 2,000 recruiters in Germany, Norway, Poland, and Romania. We asked them to evaluate the employability of candidates applying for five common positions (e.g., secretary, accounting clerk, IT staff). We randomly varied candidate characteristics including gender, education, experience, language skills, etc. We also included information about whether candidates had children and whether they were in a relationship. Additionally, we collected detailed information about respondents’ companies in question, allowing us to assess how greedy each position was.

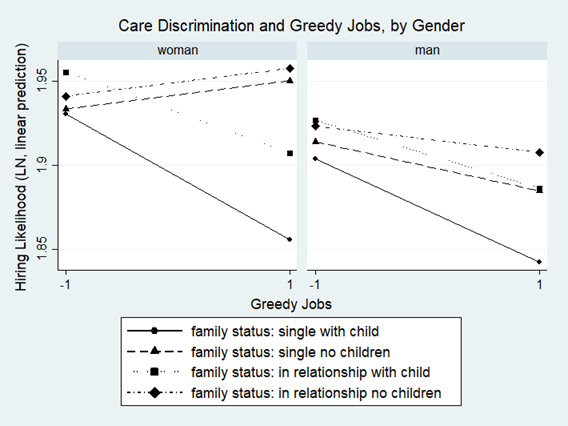

The results are best illustrated in the chart below. On the horizontal axis, we plotted a scale of job greediness: the closer to “1”, the greedier the job; the closer to “-1”, the more regular and predictable the tasks. On the vertical axis, we plotted the candidates’ chances of being hired, as assessed by recruiters: the higher the value, the better the hiring prospects.

When looking at male candidates (right panel), we see a similar pattern across family status groups. Regardless of parenthood or partnership status, the probability of being hired decreases as job greediness increases. This makes sense—greedy jobs are demanding, so recruiters are more selective.

The picture looks very different for female candidates (left panel). As job greediness increases, the hiring chances of mothers falls significantly. Recruiters, anticipating that mothers might struggle to balance caregiving with the demands of greedy jobs, are less inclined to hire them. This points to a form of caregiving-based discrimination, which disproportionately affects women.

What can be done? There are certain practices and tools at the recruitment or hiring stage which can help reduce discrimination in general, such as structured interviews, anonymized applications, clear and inclusive job descriptions, standardized evaluation criteria, and bigger recruitment panels including persons of different backgrounds. Additionally, a key solution lies in shifting workplace culture (even and especially in greedy jobs) to better support the reconciliation of professional and caregiving responsibilities for both men and women. A toolbox of flexible working arrangements includes flexible hours, remote work, compressed workweeks, job sharing, and more. These options expand the range of choices available to parents and carers, helping them navigate the difficult trade-offs between work and family responsibilities. While combining greedy jobs with flexible arrangements may seem like mixing water and fire, we believe that, at least to some degree, it is possible.