This piece discussing the gender norms and the labour market is one in a series of opinion pieces on labour market inclusion. The piece has been written by Dr Sara Ayllón. She is an Associate Professor at the Department of Economics of the University of Girona. She is a poverty scholar at heart and an applied economist by training. Her research focuses on poverty and inequality, labour market, gender, family, health and applied microeconometrics.

_____________________________

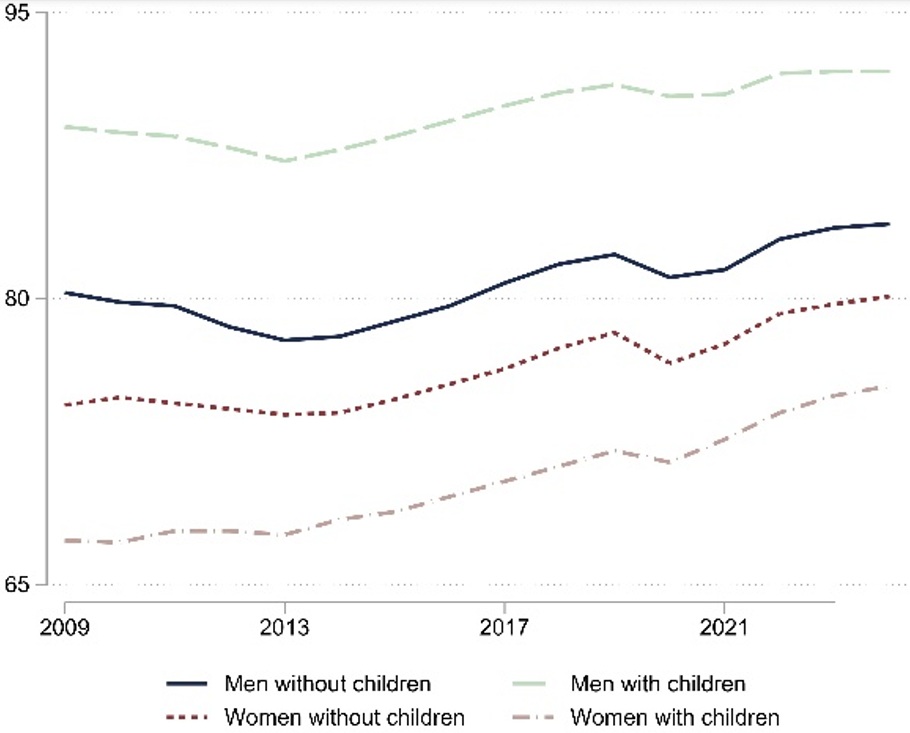

Despite decades of progress toward gender equality, the birth of a child continues to push mothers and fathers sharply to different professional paths. In 2023, women aged 25 to 54 without children were more likely to be employed than mothers in the same age group. The opposite is true for men: fathers are more likely to be employed —and to work longer hours— than their childless counterparts. Gender norms, both past and present, continue to shape the European labour market in powerful ways, influencing not just who works, but how, where, and under what conditions.

In a recent paper within the PATHS2INCLUDE project, we have examined how parenthood affects the type of employment parents engage in and the extent to which it is shaped by social norms. Using individual-level data from the European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) merged with cohort-level data from the Integrated Values Survey (IVS) for more than two decades, this research crucially asks whether more progressive gender beliefs translate into more equal work outcomes — and whether traditional norms continue to penalize mothers and reward fathers.

Figure 1. Employment rate by gender and parenthood status, European Union (27), 2009-2023

Note: Adults with and without children aged 25 to 54 in the EU–27.

Source: Own elaboration, using data from the EU-LFS.

The findings are clear and compelling. Across the continent, women — particularly those with young children — are more likely to work part-time, experience underemployment, and telework than men. Men, on the other hand, are more often employed full-time and in supervisory roles. While some of this can be explained by personal preference or economic necessity, much of it is shaped by deep-rooted cultural expectations that still assign primary caregiving to women and financial responsibility to men.

To uncover the causal effects of gender norms we used an instrumental variable approach. We took the level of religiosity in previous generations as a stand-in for traditional gender beliefs, since highly religious societies tend to promote more conservative views about family roles. Evidence reveals that the more traditional the gender norms in a region, the greater the disparities between mothers and fathers in the labour market.

Geographically, the divide is significant. Nordic regions lead the way with the most egalitarian gender norms and the smallest employment gaps between mothers and fathers. Mediterranean countries show the widest dispersion — some areas being quite progressive, others deeply traditional. Central and Eastern European nations tend to hold more conservative values, while Anglo-Saxon and Continental regions falling somewhere in between.

Interestingly, while social norms across Europe have gradually become more egalitarian over the past two decades, the transformation is uneven. Our study shows that changes in gender attitudes are happening, but slowly. Hence, exposure to counter-stereotypical behaviour is crucial since it helps dismantle gender stereotypes through social learning.

A particularly telling finding is how even in progressive households, parenthood often triggers a reversion to traditional roles. Despite holding non-traditional beliefs, many families still see mothers stepping back from work and fathers doubling down. This suggests that structural and cultural pressures still overpower individual convictions.

The implications are wide-reaching. When mothers are disproportionately nudged into part-time work or less skilled roles, they face long-term disadvantages in income, career progression, and retirement security. Fathers, meanwhile, may miss out on the emotional and developmental benefits of active caregiving. These patterns reinforce inequality not only within households, but across entire economies.

So, what can be done to close the gap? First, we must acknowledge that gender norms are not fixed. They are learned, reinforced, and, crucially, changeable. Policies and interventions that promote equal roles in caregiving and work can shift perceptions and behaviours over time. For example, expanding access to affordable childcare, encouraging paternity leave uptake, and promoting flexible work arrangements for both parents can help balance family and career responsibilities. Second, governments and employers should actively challenge stereotypes by supporting fathers who choose to be more involved at home and mothers who seek leadership or full-time roles. Highlighting diverse role models in media, education, and workplaces can accelerate the normalization of non-traditional roles. Third, policy should be tailored at the regional level. The study shows that cultural attitudes vary significantly not just between countries, but within them. Localized strategies that reflect specific values and challenges will be more effective than one-size-fits-all solutions. Finally, ongoing data collection and public reporting on gender norms and employment outcomes are essential. By measuring progress — and holding institutions accountable — we can ensure that positive change continues.

In summary, this research provides compelling evidence that gender norms still play a central role in shaping the labour market outcomes of parents across Europe. While progress is being made, parenthood remains a key turning point where inequalities deepen. Changing the narrative around work and care isn’t just a matter of fairness — it’s a prerequisite for unlocking the full potential of both women and men in the workforce. The future of equality lies not just in policy reforms, but in transforming the beliefs that underpin them.